Most learning video is subject to Ebbinghaus’ famous forgetting curve. We forget 50% of anything we learn within an hour, and it keeps fading away. Drama has the potential to confound this because of its ability to engage emotion.

After 35 years of making drama for learning, I can say with confidence that despite the amount of drama that is produced in the L&D world, there is limited knowledge out there about how drama actually works. Which means I’m often asked to sort out problems in a drama project at too late a stage because the basics of the design have already been agreed and signed-off.

Wouldn’t it be great if there were a little handbook with all the core principles and techniques of drama designed for the L&D practitioner? Fortunately, there is, because I’ve just written it. It’s called Watch & Learn, and it’s just 18,000 words long with summary learning points at the end of each chapter. My aspiration is for it becomes a go-to reference for anyone in L&D working on a drama project. If we can make this knowledge a commonplace there’s no doubt that the quality of learning drama will improve.

Core Messages

What are the main mistakes and misconceptions in L&D around drama production? Film and TV is a seductive medium, so a lot of people, even seasoned pros get carried away with the superficial aspects and go awry. That first Suicide Squad movie is a good example – a massive budget, with great stars, but even after the studio re-edited it twice, it’s still a mess. And we see this in L&D when people get too excited with the toys in the sandbox. Someone sees an exciting technique on TV and incorporates it into their project. It probably looked good in the pitch to the client – but very often the technique is no longer appropriate in the new context.

The most powerful techniques are those that don’t draw attention to themselves. Naturally, these are the ones that people without training in filmmaking are least aware of – except as an audience – when we are all incredibly sensitive to and critical of poor filmmaking.

Another basic error I see is scripts which are written as “this happened, that happened” – explaining what the events are. This isn’t storytelling, it’s exposition.

Which is hardly surprising, as exposition is one of the main modes used in learning design. But in drama, exposition is something we try to minimise and avoid. Exposition is ‘tell don’t show’.

To create a drama, we have to model characters and put them in situations which are challenging. Situations in which they must make moral choices. And the harder the choice, the better. Watching drama is an active function. Yes, people watch drama to relax, but their imaginations are active – because they see characters in challenging situations and ask themselves what they would do faced with such challenges.

The function of drama in learning

So, what is drama good for in learning? What it’s not good for is teaching details of a subject. We might show a scene that involves a procedure, or some actions that fulfil compliance criteria, but drama isn’t much good for teaching these things.

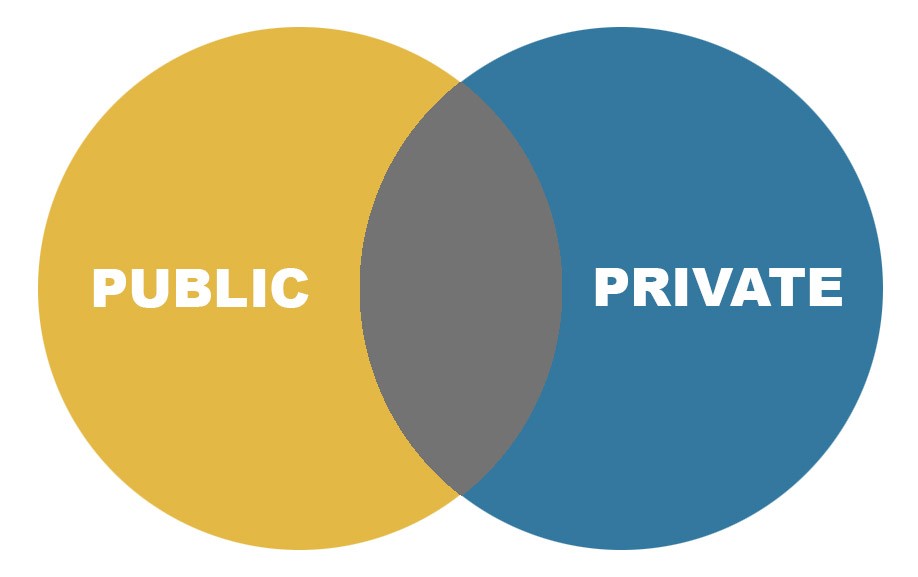

Drama’s strength is in teaching us how to behave at work. We are complex, emotional beings, who need to control and compromise our feelings to be able to function in teams of people who are, after all, colleagues and not necessarily our friends. The part of human experience where learning drama works best can be represented by a Venn diagram overlap of public and private.

The main applications, therefore, are anything that involves a behavioural element, such as diversity and inclusion, personnel management and for jobs that are emotionally challenging, such as healthcare. But equally, we can bring drama to bear on compliance issues, because without addressing the attitudes that lead to lack of compliance, compliance training is literal box-ticking.

Research

I’ve just been reading about some research-based analysis of the role of emotion in learning that, to me, throws light on the use of video drama. In his Plan B blog, Donald Clark writes about the work of neuroscientist Antonio Damasio and associate professor of education, psychology, and neuroscience Mary Immordino?Yang:

“In learning, what are taken as necessary and important cognitive functions – attention, memory, decision-making, motivation, and social functioning – are deeply affected by emotion and seated in emotion. Reason rarely exists without emotion and the application of reason is always guided by emotion. Emotional thought is therefore the platform for learning.

The problem in learning is to focus too much on the rational domain, forgetting that it takes place in an emotionally embedded setting. It also leads to devaluing emotional self-regulation and the ability to apply what one learns to new situations and the real world.”

In the light of this, I would suggest that, particularly as remote working becomes more common, video drama offers a useful means to speak to the emotions of a group in a legible and immediate format.

Technique

In Watch & Learn, as well as addressing these core points, I describe a host of technique and theory that can be applied to any drama project. So, whether you’re a learning designer, or someone looking to commission some learning drama, the book is designed to quickly give you a good deal of confidence and technique to with which to work. Break a leg!

Webinar

To find out more, check out the recording of my recent webinar about Watch & Learn.